Technology's Contribution to Sustainability

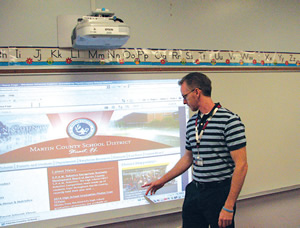

PHOTO COURTESY OF EPSON

“When the subject of sustainability comes up, there are two issues,” says Mike Raible, founder of Charlotte, N.C.-based The School Solutions Group, which helps school districts find innovative solutions to issues. “One is, organizationally, what is sustainable? In other words, what can go in our continual funding to sustain in terms of effort and culture? The other is sustainability in terms of green philosophy — what is environmentally sustainable?”

This article takes a look at both issues from the IT perspective, appreciating the efforts of the IT team, as Missy Trumpler, LEED-AP, GGP, notes: “Now that facilities have shifted to energy management systems and building automation systems, we depend heavily on IT staff to make sure energy management software is downloaded and running; different companies’ controls are communicating, functioning properly and giving information; and that updates are occurring.” Trumpler is energy manager for Martin County School District (MCSD) in Stuart, Fla.

Software that keeps buildings running efficiently

Software falls into two categories, that which keeps building running efficiently and that which keeps education running smoothly. Software that keeps buildings running efficiently is classified as sustainability in terms of green philosophy. It’s powerful stuff.

Turning off computers: “We have a program that turns the computers on every morning, shuts them down at the end of the day and conducts updates,” says Marilyn Gavitt, MCSD’s coordinator of Digital Learning. “We have reduced energy consumption and have saved the districts tens of thousands of dollars.” This is a fairly common practice among school districts. At MCSD, they go a step further, asking teachers to turn off monitors at the end of every day. “It costs $30 per year to power a single monitor,” Trumpler says. “Multiply that by hundreds of computers. You can see that making sure they’re turned off results in huge savings.”

MCSD has recently begun investing in Epson BrightLink interactive projectors. Gavitt notes that, like computers, they can go on the network and be centrally controlled from the district for energy savings. “We’re waiting for the final step to accomplish that,” she says.

Turning off HVAC systems: MCSD, like many other districts, uses software to shut off heating and air conditioning during winter, summer and other breaks. In addition, in summer, staff works four 10-hour days so that energy can be saved three days in a row.

Turning off lights: Another sustainable practice MCSD has implemented is going dark; that is, turning off all lights 30 minutes after the last custodian leaves a campus, including parking lot lights. Trumpler notes that it saves energy but is also a tactical advantage according to the Department of Homeland Security.

Providing data: Trumpler appreciates software that provides facilities trending data. “Without the information,” she notes, “we would not be able to manage energy as effectively and save the amounts of money we’ve been able to save. And the savings will hopefully be greater as we’re able to integrate more and invest in more software that gives us information.”

Software that keeps education running efficiently

Software that keeps education running efficiently is classified as organizational sustainability, that which sustains effort and culture. Many districts are already on board with a number of these programs, such as electronic grade books, electronic transcripts, time and attendance systems, and document management systems, which save both postage and paper costs.

School board meetings: MCSD is using BoardDocs for board meeting preparation. It’s a cloud-based program that allows districts to create and manage packets, access information and conduct meetings. “We can make updates quickly without reprinting the agenda,” Gavitt notes.

Email, calendars and documents: Like many districts, Kettering City School District (KCSD) in Ohio, is moving as much as possible to a paperless environment. To that end, the district is using Google Apps for Education, a free program for web-based email, calendar and documents, allowing for collaborative study anytime, anywhere. “Notes for meetings and professional development are shared here, as are discipline referrals and weekly staff newsletters,” says Chris Merritt, KCSD’s interim director of Technology Services.

“We knew we wanted to provide students with email accounts,” Merritt continues. “Outlook would have cost thousands and thousands of dollars. Google Apps saved us that money because it’s free. Plus, it is all sandboxed. We have complete control over the email accounts. People from outside can’t email in to students and students can’t email out.”

Hardware considerations

Hardware, too, is making a firm contribution to sustainability. Like software, it requires the expertise of the IT team to get it up and running. Here’s what’s going on.

Quality: “Every school has data closets with routers, servers and pieces of technological equipment that generate heat, and we have to build them in the schools,” says Andrew LaRowe, president of BAISCA, LLC, which specializes in the collection of data and the development of reports related to facility issues in school districts. “The closets are designed with supplemental air conditioning because they get hot and, if they get too hot, the equipment breaks down. As advances are made in equipment, we’ll work our way out of needing supplemental air conditioning.”

And server advances are being made. “We’re moving to solid state drives, which don’t have to spin motors or have heat created by friction,” says Bill Brown, executive director of Education Technology Services for Greenville County Schools (GCS) in South Carolina. “They fail less frequently than hard disk drives. Plus, we’re able to store more data on the servers than we were seven years ago, so we’re using less of them, which means we’re using less energy.”

Other technology areas are seeing advances as well. For example, the Bright-Links projectors mentioned earlier are more durable than projectors made in the past, so they last longer. In addition, Gavitt, likes them because the lamps cost less than the district’s previous projectors and educators can choose the software they want to use with the projectors. All this results in a lower cost of ownership.

Powering student-owned equipment: This is an interesting hardware situation, because it involves energy consumption — on student-owned devices. “We’re looking at installing kiosks so students can power up while they’re in class,” says Brown. He notes that most of GCS’s schools have been rebuilt in the past 10 years, but classrooms still have only about 10 outlets each, while there may be 30 devices that need to be charged. Laptops have 2.5- to 4-hour battery lives and cell phone batteries may last a day, but quickly drain as they try to reach cell phone towers as radio waves don’t easily enter the schools. “We have to consider this in the future in terms of energy usage and sustainability, and we have to consider our equipment and the equipment coming in,” he observes. “If we want students to use their own devices in an instructional environment, we have to provide the power; we can’t assume that they’ll bring their devices charged and ready to go,” he sums.

Balancing lifecycle costs: This is a humdinger of a sustainability issue, as it is multi-faceted. First and foremost, says Trumpler, you want to purchase efficient equipment. But if it doesn’t have a long life span, you lose out on efficiency. Then there’s the care of the equipment you’ve purchased. “We carefully monitor and provide our equipment with a stable environment,” says Brown, “because consistent temperature and humidity ensures longevity. We’re able to push our equipment to seven to nine year lifespans, as opposed to the more typical three to five year, except for mission-critical servers, which are changed out at five years according to manufacturer agreements.”

Lifecycle costs also including a consideration of availability vs. an outage. “You can’t look at lifecycle costs solely from a first-cost perspective; you have to consider the cost of providing service,” says Brown. “For example, we are able to provide four 9s. That means we’re operational 99.99 percent of the time. We’d like to be at five 9s: 99.999 percent. How much would we lose if we weren’t operational? Imagine 6,000 teachers not able to access grade books for an entire day. Imagine our Trane monitoring equipment not being able to send email notifications to facilities staff.”

Lifecycle costs also include the ability of IT staff to support and maintain the equipment purchased. For example, KCS is investing in Chromebooks for a one-to-one initiative. A factor in the decision to go with this device is that they’re easy to manage from the Google administration panel and they automatically update with the Chrome operating system. “With Chromebooks,” says Merritt, “we can scale up but don’t necessarily have to add personnel. If we have to add staff, ramping up can become cost prohibitive and possibly unsustainable in the future when relying on funding sources.”

KCS is purchasing the computers with grant money, which raises the question of being able to sustain future usage as they complete their lifecycles. Merritt indicates that the computers cost less than $250 each, compared to almost $1,000 for Macbook Pros, and that they cost less than $150 to repair. “We’re saving huge by buying devices that cost less,” he explains, “and that will help with sustainability.

“We’re not just buying the least expensive piece of equipment,” Merritt continues. “The Chrome platform provides everything we need without the cost of full-fledged pcs or Macs, at a price point that is sustainable for us. And Google Apps for Education connects seamlessly with the Chrome operating system, which is a Google system as well.”

Equipment refreshing: Many districts refresh computers on a schedule. For example, MCSD refreshes every four years KCSD has an informal, five-year refresh cycle, although Merritt notes that, because technology changes so fast, it’s difficult to have a fixed replacement schedule. The sustainability challenge refreshing raises is, again, the ability to continue what has been begun. “First of all,” says Raible, “you have a 10 percent break/fix cost per year. Then you have to account for growth. For example, Charlotte-Mecklinburg Schools in North Carolina has 3,000 to 5,000 new students per year. That’s a substantial purchase on top of refreshing for the entire student body which, for them, is more than 130,000 units.”

There’s also equity to consider. Let’s say you replace 20 percent of the devices every year on a five-year cycle. Some parents are going to ask, “Why does my student’s school have an older computer but the other school has new computers?” Plus there are differentials to address, such as older devices not having the capability and capacity that new devices have, or the ability to accommodate newer programs, or the memory. “All that rolls into the discussion of sustainability,” says Raible. “Therefore, you have to plan for the initial purchase, but also how you’re going to continue the program through time. If you don’t it won’t be sustainable.”

Districts are doing much in the way of sustainability, in terms of both organizational and environmental sustainability. “As a team, we continually explore ways to reduce our energy consumption,” notes Gavitt. “We have to be aware and seek opportunities. One thing is sure: We couldn’t do it without the IT team and IT integration.”

This article originally appeared in the issue of .