Energy Savings: Insights and Innovation

- By Jason Mellard, Nathan Hart

- 12/01/16

PHOTO © SELSO GARCIA

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection

Agency (EPA), the cost of energy is the

second highest operating expense for school districts

around the country after personnel. Furthermore,

the EPA estimates that 25 percent of

energy use in schools is wasted. As U.S. schools

continue to face increasing budget pressures,

implementing strategies for energy savings can

have a significant positive impact on the bottom

line for school districts. By implementing policies

for energy use reduction in new construction,

renovation as well as in building operations and

maintenance, school districts can direct much-needed

funds to student services and personnel.

Effective use of bond dollars in new construction

and renovation provides the greatest

impact on energy savings over the life of a

building. Energy efficient, sustainable design

must be incorporated from a project’s inception

to be most effective in decreasing life cycle

costs. Site selection, building orientation, mechanical

systems, efficient building envelopes

and low-maintenance materials are some of the

key considerations in campus design.

Additionally, the use of energy modeling early

in design can help inform big picture design decisions

from the outset regarding orientation and

sunlight. Finally, close collaboration between the

architect, consultants (i.e. MPE engineer, structural

engineer, civil engineer) and contractor fosters

good communication and helps to ensure a

whole systems approach to the design.

PHOTO © INDEPENDENCE PROFESSIONAL PHOTO

Seeing the light

According to the EPA, artificial lighting

consumes an average of 25 percent of a school’s

energy. Being considerate of the mix of artificial

and natural lighting in school design can have

a significant impact on energy costs. Automatic

daylight harvesting, vacancy sensors and dual

controls in the classrooms limit the number of

switches users need to control. In recent years,

LED lighting has become more competitive in

cost when compared to fluorescent lighting at

a fraction of the energy cost. Dimming is more

easily incorporated in LED systems and additional

wiring costs are minimized.

In addition to looking for ways to minimize

costs in artificial lighting, priority should also be

placed on designing to maximize natural light

in schools. Natural light in classrooms has been

shown to increase test scores and student focus.

In fact, a study by the Northwest Energy Alliance found that students in rooms with the most diffuse and glare-fee daylight

improved performance on standardized tests by up to 26 percent.

PHOTO © CHARLES DAVIS SMITH

Air and Temperature Control

After lighting, mechanical systems account for the most energy

usage in buildings. Additionally, high-quality indoor air has been

shown to have the greatest effect on student performance and attendance

along with natural lighting. HVAC system selection should

take into account the size, shape and program of the building. There

are many different mechanical system types available. The best system

is the one that: 1) can be properly maintained by the district

maintenance staff, 2) is energy efficient, 3) will fit the site constraints

and 4) will meet the budget limitations of the project. With any mechanical

system type selection, it is important to be sure to meet or

surpass the minimum outside air ventilation requirements for the

space. This outside air requirement often places the largest load on

HVAC systems and needs to be considered as an integral part of any

system. Pre-treat systems, energy recovery ventilation, and return air

tempering should all be taken into consideration.

Some of the more energy efficient systems utilized in the Southern

United States include Geothermal (Ground Source) Heat Pumps

and Variable Refrigerant Flow (VRF) systems. However, these systems

can sometimes be more expensive to incorporate. Some of

the less expensive, historically less efficient HVAC systems such as

packaged Roof-Top Units (RTUs) now have options for significantly

higher efficient equipment offerings. Instead of settling for 13 Seasonal

Energy Efficiency Ratio (SEER) efficient RTUs, higher efficient

20-23 SEER units can be installed for a minor cost increase per

unit. Through the use of variable speed motors, multi-stage compressors,

and other improvements, these new systems can make a

dramatic difference in a building’s energy usage, especially in an

equipment replacement project.

PHOTO © CHARLES DAVIS SMITH

After careful siting of the building and selection of appropriate

lighting and HVAC systems, the building envelope itself has the potential

to save energy dollars. High performance walls, openings, and

roof assemblies are continuously improving through code requirements

and competition. Building codes are requiring not only higher

R-values in roofs and walls, but also continuous insulation (unbroken

by studs or framing) for new construction. New technologies such as

Insulated Concrete Form (ICF) walls can be considered as well.

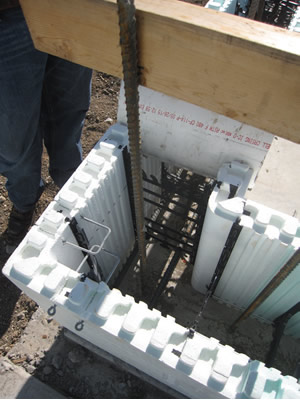

Insulated Concrete Form exterior walls (ICF) are being more

widely used in school design. This system is composed of two layers

of rigid insulation formwork, which is filled with a layer of concrete

poured in between. These walls provide up to an R-40 insulation

value, reducing heating and cooling loads significantly. They reduce

indoor allergens by limiting air infiltration and allow for a quieter

indoor environment. ICF walls are inherently more rigid and durable

when it comes to impact resistance, providing greater protection

from tornadoes, hurricanes and fires. The concrete also has a longer

lifespan than conventional wall construction, creates less waste

and increases the speed of construction beyond the typical pace for

CMU or stud framed construction.

In conjunction with the wall assembly, a designer

should evaluate heat transfer through the roof, crawl space

and window openings. These should have an R-value that

is complementary to the walls for the overall envelope to be

the most effective. Consider increasing the roof insulation

design from R-20 to an R-30 highly reflective roof in order

to ensure the energy efficiency of the roof approached that

of the high performing walls. Proper flashing and sealing

of windows reduces air and water infiltration. It is also

important to select glazing with a low solar heat gain and

shading coefficient. For optimal performance, exterior

sun control should be provided on openings through the

use of louvers, sun shades, and overhangs.

Frisco ISD’s Independence High School designed by

Corgan, is a 2,100-student comprehensive high school

designed with insulated concrete form wall construction.

In combination with a geothermal heating and

cooling system, LED lighting, and careful building

layout and siting, the campus uses over 50 percent less

energy than Frisco ISD’s similar-sized Centennial high

school, built eleven years prior. The district has opened

an additional nine other ICF schools since 2014, and has

four more currently under construction.

PHOTO COURTESY OF CORGAN

Sealing the Envelope. Insulated Concrete Form

(ICF) exterior walls provide high R values and

continuous insulation due to the lack of studs and

framing. They are becoming more common in

school design. The ICF system is composed of two

layers of rigid insulation formwork that is filled with

a layer of concrete poured in between. The walls

provide up to an R-40 insulation value, reducing

heating and cooling loads significantly. They reduce

indoor allergens by limiting air infiltration and allow

for a quieter indoor environment.

It Takes a Village

When developing district standards for building construction

and maintenance, one should do so in tandem

with the staff “holding the tools.” The staff knows the

school best; they should be included in design development

and trained on new technologies. “Education is key to empowering

maintenance staff,” says Jerry Palermo, energy

manager for Grand Prairie Independent School District.

“Understand that after all the engineers and contractors are

gone, they are the ones that have to care for the building.”

A successful energy management plan involves not only

maintenance and operations staff, but also administrators, teachers, students, the community and designers. Education and awareness

are powerful tools to create buy-in from everyone. Clear goals and

baseline analysis allow for clear measurement of savings over time. To

aid in this effort for their district, both Frisco ISD and Arlington ISD have

developed websites where students, staff and the community can view

detailed data regarding water, natural gas and electricity consumption

of the district’s buildings. Sustainable practices and systems can also be

impactful teaching tools for students. Leaders should provide transparency

to students and teachers as to the power usage they generate.

Systematic energy audits can also be effective in reminding users

of the impact they have to control energy costs. Eliminating

microwaves, space heaters, refrigerators and printers from classrooms,

turning off computers and lights throughout buildings and

dialing back the thermostat during off-peak hours have a big effect

on the bottom line. A staff member should walk every roof a school

periodically to ensure their school is not underperforming.

PHOTO COURTESY OF CORGAN

Finally, paying attention to the energy bill is important. One

should compare current trends with those from the past to set a

baseline for energy saving strategies and potential audits or facility

upgrades. To aid in this comparison, energy consumption meters

can be provided at the main electrical, water, and gas service to a

facility and monitored to closely track consumption. Energy penalties

can be incurred without notice, such as when a school’s power

factor drops below a certain power quality percentage (usually below

90 percent). Power factor capacitors allow a building to utilize

power more efficiently and pay for themselves quickly by reducing

penalties from energy providers.

Maintenance is Key

A 2011 McGraw-Hill study noted that the average age of school

buildings in the United States is 42 years — which is nearly the expected

serviceable lifespan of a school building. Facility assessments

can help to determine whether pouring additional money into an existing

building will pay off in the long run. Depending on the extent

of work proposed, existing building codes may require increasing the

amount of outside air into the building (potentially requiring new air

handlers and increased duct sizes), upgrading lighting controls and

fixtures and upgrading plumbing fixtures to meet new water usage

standards. Administrators should use renovations as targeted opportunities

to upgrade existing systems for greater performance over

time. For instance, one might defer a total building overhaul and instead

replace an aging roof assembly with a more energy-efficient one.

Many grants and incentives are also available for school districts.

Rebates are available for converting existing lighting systems

to current standards or replacing older HVAC equipment with

newer and more efficient equipment. The State of Texas, through

the State Energy Conservation Office (SECO), has provided multiple

grants to smaller districts to replace older lighting and HVAC

systems and provide solar power. One of the larger electrical distributors

in Texas has provided rebates for higher efficiency HVAC

equipment, lighting, high efficiency roof, high efficiency window

glazing, and other energy efficient building systems. Grand Prairie

ISD is currently closing out their summer 2016 projects with the

Oncor energy efficiency incentive program, and the utility company

will compensate GPISD upon Oncor’s inspection of the energy saving

measures incorporated into the design.

PHOTO COURTESY OF CORGAN

Accurate and accessible as-built documents, product manuals

and warranties allow for ease of troubleshooting and maintenance

schedules. Recordkeeping software, such as the Project Documentation

Software by Ex3 Facility Solutions, can pinpoint specific

equipment types, controls and locations installed in each school,

reducing time and road-blocks to properly maintain facilities.

In Conclusion

Energy efficient design can have a truly positive effect on our

schools. In these times of increased financial scarcity and scrutiny,

thoughtful approaches to energy saving can help direct resources

back to personnel and students, creating a meaningful impact on

students, schools, districts and communities.

This article originally appeared in the issue of .