Sustainability: A Whole-Systems Approach

Sustainability is not something that gets checked off a list and forgotten about. Colleges today are integrating green practices into everything from coursework to campus life to the town beyond the campus walls. The practice helps attract students, save money and meet carbon footprint goals. College Planning & Management profiles three schools that eat, breathe and sleep green.

COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY

PHOTOS COURTESY OF COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY PHOTOGRAPHY

Taking It to the Streets

Sustainability is woven into Colorado State University’s (CSU) very DNA, according to co-chair of the president’s sustainability committee, Tonie Miyamoto. “Eighty-six percent of our students and 83 percent of our staff and faculty say that sustainability is important or very important to them,” she reports. As a result, the university offers majors and minors in the subject at all eight of their colleges. Sustainability-related research is conducted in more than 90 percent of the academic departments. Students in any major — think English, math, statistics or art — can get a minor in sustainability and work on it through an interdisciplinary lens. “We want to stress that sustainability has a place in whatever field or career a student is attracted to,” Miyamoto says.

CSU Fort Collins is even experimenting with getting students involved before their first term begins. Their eight-week Bridge Scholars Program provides residential college-life experiences to first-generation or underrepresented incoming freshmen. Students work on a real-world project that benefits the city of Fort Collins while sharpening their researching, writing and presentation skills.

“I think of it as a cosmic Venn diagram,” says instructor Paul Hellmund. “In one circle are the very real resiliency issues faced by the Fort Collins community, the other is made up of students who want to make a difference now, not after graduation in four years. In the middle is this workshop.”

The summer of 2017 included four different sustainability projects. One started tackling Fort Collins’ substantial food waste problem; another looked at the current state of the city’s community health. A third project explored options to maximize health and wellness on a newly purchased, 20-acre lot that surrounds a local health clinic. The final project explores Fort Collins’ lowerincome and underrepresented populations’ attitudes towards active transportation like walking, biking and bus use.

The students do every part of the project independently. They work with sponsors/clients to refine questions, conduct research, write proposals and give presentations. So far, the output has been well received. “I get emails from stakeholders that are amazed at the work’s sophistication, particularly when you consider that these students were just at their senior prom a month prior,” says Hellmund. “This is a great way to bring a small, private New England-college experience to a large, public university.”

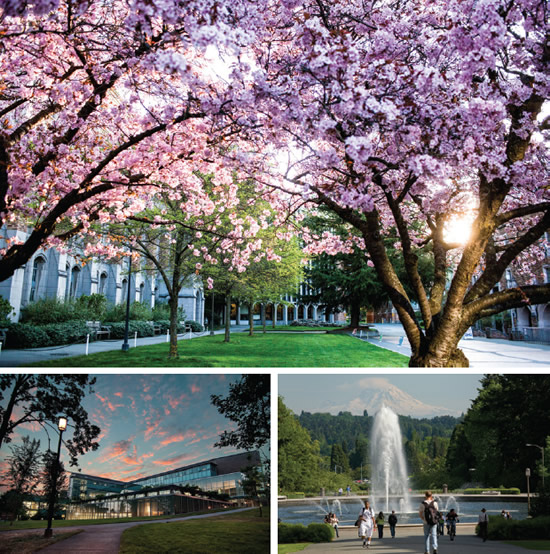

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON

PHOTOS © UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON

Greening Up the Wall

Sustainability is “near and dear to our hearts,” according to the University of Washington’s (UW) sustainability director Claudia Frere-Anderson. More than just talk, parts of the school’s campuses functions as living laboratories, hosting a broad range of projects that address operational, education and research challenges and opportunities through a green lens. These projects provide innovative solutions for the school, the community and the state and may involve students, faculty, staff or a combination. The projects are funded through grants like the Campus Sustainability Fund and Green Seed Fund.

“The Campus Sustainability Fund is in its seventh year and has funded $2 million in projects,” reports Frere-Anderson. She sees the work as a win/win as “students come up with cool ideas and the university benefits from innovation and some cool new infrastructure.”

Living lab projects include field work in Alaska, wetlands development at UW Bothell and a prairie trail in UW Tacoma. The Seattle campus includes four different projects, including the Gould Hall Green Wall at the College of Built Environments.

Run by Nancy Rottle, associate professor of Landscape Architecture, seven students from four different disciplines created a biodiversity green wall, edible green screen and water harvesting demonstration project. The work will “potentially show the capacity of building skins to ecologically contribute to the urban environment,” according to Rottle on the UW website. “We want to use the project as a billboard for new sustainable practices, and to discover to what extent green walls and screens can help promote biodiversity, produce food and reduce energy use. By harvesting water to irrigate the green wall, the project will reduce potable consumption and may lessen storm water impacts.”

Launched in 2012, the project won an honorable mention in the What Makes It Green competition sponsored by Seattle’s chapter of the AIA. Five years later, the green wall continues to serve as a teaching tool for a variety of disciplines including construction, horticulture and design. The water catchment piece allows for ongoing research.

Even if students don’t engage with any of the living lab projects they still have an opportunity to explore sustainability. Sean Schmidt, sustainability specialist, runs programs for freshmen that introduce them to the topic and then lets them explore how it fits into any degree. “I bring in guest speakers and representatives from organizations like Boeing and the General Services Administration,” he says. The idea is to give students a green vocabulary that helps them bring innovative ideas with them wherever they land after graduation. “They can articulate how resource and process efficiency reduces costs.”

STANFORD UNIVERSITY

PHOTO © TONY JIN

The Green Thing Is the Right Thing

After 10 years of strong focus, sustainability is a core value that Fahmida Ahmed, director of Stanford’s Office of Sustainability proudly says is, “integrated into every aspect of campus life.” Achievements include Stanford Energy System Innovations (SESI) which electrified the campus and gets 65 percent of its power from renewable sources like solar. Most of that solar comes from a dedicated facility built in Southern California.

The move has allowed the school to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 68 percent. “There’s been a real transformation in the last couple of years,” says Ahmed, “and huge positive reinforcement from the administration. Ten to 15 years ago there was a more of an ‘us versus them’ attitude but now everybody wants to do the right thing.”

That “right thing” includes more than 1,000 sustainability courses taught across Stanford’s seven different schools. “We approach teaching sustainability through a systems perspective,” explains Dean Pam Matson. “It’s not just about the environment but [also] about human well-being.”

The school is also trying to change the behaviors of students, faculty and staff. Their focus on getting the campus population out of single-driver cars caused a drop in lone drivers from 72 percent to 50 percent. A project called My Cardinal Green offers even more opportunity for changed behavior. This engagement program evaluates a person’s commitment to sustainability and assigns a “shade of green.” It then generates a specific, tailored list of what an individual can do to be greener.

“You get points for completing a given activity and a cash incentive,” says Ahmed. Actions can be as simple as turning off lights before leaving the office or taking shorter showers to more complicated tasks like motivating a business manager to start a green team. This year saw 700 participants, and Ahmed hopes for more. “Sustainability isn’t just state-of-the-art HVAC or energy efficiency but individuals armed with tools and information. They want to see that their actions matter, and programs like My Cardinal Green does that.”

The school’s strong commitment and verifiable outcomes resulted in Stanford Earning a Sustainability Tracking, Assessment & Rating System (STARS) Platinum status from the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education (AASHE).

This article originally appeared in the issue of .