Storm Shelters’ Growing Importance in Schools

Across the country, building codes are being implemented as solutions to respond to increasingly severe weather events. Model building codes, specifically the International Building Code (IBC), contain requirements to incorporate a storm shelter as part of public buildings, including K-12 schools. Each jurisdiction adopts the model building codes with differing modifications, but the inclusion of the storm shelter requirement is becoming more common as new versions of the building codes are adopted and weather events like tornadoes continue to rise.

Reliable storm shelters must include the engineering necessary to ensure safety, comply with required guidelines and create comfort during emergencies. As one of the largest educational architecture and engineering firms in the country, Wold Architects and Engineers has extensive experience designing storm shelters in K-12 schools and learning centers to create an imperative line of defense that protects work crews, staff and students during emergency situations.

Based on conversations with districts across the US, especially in areas where storm shelters are becoming more critical to design and include, the following are some of the most common questions and considerations for incorporating a storm shelter that meets IBC requirements into K-12 school designs.

What is required by the IBC, and why is it important?

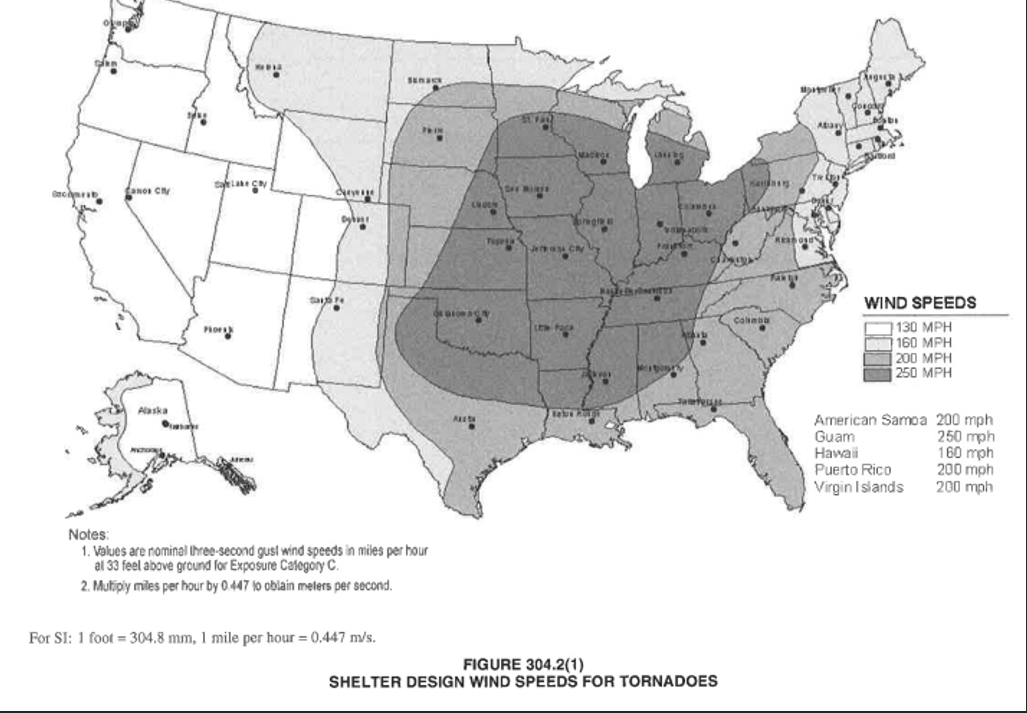

It’s important to note that the model building code does not require the implementation of a storm shelter across the entire United States, even though it’s a nice safety addition to include. Currently, the IBC requirement references a map, Figure 304.2 of the International Code Council 500 design manual, that shows wind speeds for tornados, and the requirements of the model building codes mandate a storm shelter where wind speeds reach 250 miles per hour.

Figure 304.2 of the International Code Council 500 design manual showing required storm shelter areas.

For buildings that fall under the designated areas, Chapter 4, Section 423.5 of the IBC “requires storm shelters for Group E occupancies (schools) with an occupant load of 50 or more.” Each local jurisdiction adopts the model codes with modifications, so the inclusion of a storm shelter may or may not be required regardless of whether schools with 50+ occupants fall within the IBC-mandated area. Districts can also voluntarily include a storm shelter, if desired, to ensure staff and students’ safety.

This requirement is especially important because public buildings, like schools, contain many occupants for extended periods of time. If a tornado strikes a school, there are many safety concerns and vulnerable occupants, and storm shelters can help reduce the impact of wind and flying debris from reaching students and staff.

What should districts know about designing for storm shelter inclusion?

First and foremost, confirm whether a storm shelter is required by the district’s jurisdiction. This allows schools to plan for a storm shelter, both in terms of space and cost, from the onset of a project. Altering a project in design to incorporate a storm shelter can prove challenging.

The IBC also recommends the actual design requirements of storm shelters be guided by the ICC 500 standard, so reviewing and understanding it will help districts plan. Additional considerations for storm shelter design include:

- Optimize efficiency: It’s common to use a space already being designed to double as a storm shelter. For example, if you are adding a gymnasium, design the gym to function both as a recreation space and a storm shelter. Keep in mind, the required size of a storm shelter must be based on the occupancy of the entire building, not just the planned addition. A small room, like a bathroom or weight room, may not be large enough to satisfy the requirements.

- The space’s contents matter: The use of the planned storm shelter space(s) also impacts the required size. For example, a gym with few interior walls and fixed equipment can fit more people per square foot than a densely packed storage room. For this reason, consider using more open areas as storm shelters to build a more efficient space.

- Bathrooms are required: You will need to provide toilet rooms in the storm shelter. The number of fixtures will be determined by the number of required occupants.

- Ensure redundant utilities: The storm shelter needs to continue to operate even if the rest of the building is destroyed. Therefore, the shelter will need to have its own water and sanitary system to support the use of restrooms and drinking water. It will also need a way to provide dedicated power, such as a generator or batteries.

- There must be ventilation: Two strategies for providing the required ventilation include the primary ventilation system operating on a backup power source or natural ventilation. Natural ventilation, specifically, can be a great way to help keep costs down. This approach provides fresh air but not tempered air. In essence, the storm shelter would have a series of storm-protected louvers that can be opened to provide fresh air to the occupants. This allows schools to have a much smaller generator because it does not need to back up the primary ventilation system.

- Budget for it: Storm shelters can be expensive to construct - they may raise the cost of the space by up to 50 percent! Prices rise due to increased structural requirements to resist wind loads, redundant building systems, protected openings, necessary third-party reviews and special inspections. Budgeting for these spaces is a top priority to ensure the space meets all requirements and serves its function in the best possible way.

While these are some of the primary requirements to consider, it's important to review all of the ICC 500 standards and understand any modifications by the district’s jurisdiction.

Would an existing building that’s built with concrete/masonry satisfy the storm shelter requirements?

It is extremely unlikely that an existing building could be certified as a storm shelter. Typical building codes do not require buildings to be designed to resist 250 mph winds and the associated uplift potential, as well as protection from flying debris that is often experienced during a tornado event. In addition, most existing buildings do not have the required redundant utilities. Although the construction of an existing building may look robust enough to be a storm shelter, it will not meet the requirements of the code.

This can be challenging if districts are planning a smaller addition to an existing building in which they want a lot of glazing and/or openings. Depending on location and jurisdiction, the code may require that schools build a storm shelter until they have met the occupancy requirements. For example, in Minnesota, let’s say a storm shelter is required to be 4,000 square feet to house all occupants of a facility. If the planned addition is 2,000 square feet, the code does not require the school to build a larger addition. However, the code does require that the first addition of 2,000 square feet and the next future addition (up to another 2,000 square feet) will need to be a storm shelter.

Does a storm shelter need to look like a bunker?

Fortunately, there are lots of ways to design storm shelters that are attractive and comfortable to occupy. Many products on the market can aid in this effort, too. Storm-rated windows are a great strategy to continue to allow natural light into spaces while being protected.

Storm shelter featuring storm-rated windows at North Star Elementary School, White Bear Lake Area Schools, in Hugo, Minn.

Collaborating with a design partner that has significant storm shelter experience is critical for success. The end result will be a safe, cost-effective, functional and inviting space that doesn't look or feel like a “shelter.” An ultimately successful storm shelter will be hard to identify by the general public as a shelter but extremely safe for those occupying the space.