At First Glance

PHOTO © UNILOCK

Well-designed and -equipped outdoor spaces can help achieve a number of things, such as providing practical, contextual solutions; attracting more use to targeted areas of a campus; and reaching out to surrounding communities.

Guiding outdoor areas toward those kinds of objectives and others can entail subtle, incremental changes or major design and construction projects. There are many examples of spaces making a tangible difference, including the new Manhattanville campus of Columbia University in New York City, Black Hills State University in Rapid City, SD, and Philadelphia’s Drexel University, among others.

New York, New York

PHOTO © SCOTT BERMAN

Columbia’s Manhattanville complex, a few blocks from the university’s main campus, is in the midst of a construction program that is remaking a 17-acre site. Project designer Kimberly Cooper, associate of landscape architecture firm James Corner Field Operations, says a guiding principle of the project is a campus that “opens its doors out to the community,” and is engaged in “interaction with its community,” as opposed to an urban campus secluded and separate from its surroundings.

The master plan seems to not just comply with, but also to embrace and even celebrate, city zoning rules that require public portions for such developments. The idea of openness, for example, is expressed through a gradual transition from the streetscape into and through Manhattanville’s Jerome L. Green Science Center, which features high expanses of glass curtain wall leading to a great lobby. The lobby cuts through the building from east to west, displaying the campus’ location between Broadway and its elevated subway line to the east and the Hudson River, about two blocks to the west.

PHOTO © SCOTT BERMAN

On the building’s west side, a tree-lined plaza — along with the campus’ perimeter sidewalks, also tree lined — together serve as a conceptual gateway to Manhattanville’s “network of green spaces.” The gateway leads pedestrians, both students and the wider public, into and through the campus along tree-lined landscaped paths, Cooper says.

At the center, at a point mid-block on the campus grid, will sit a green square for gathering and sitting. It’s a circulation sequence that could be described, in either direction, as streetscape-gateway-paths-green square. As Cooper says, the configuration replicates classic campus walks and quads.

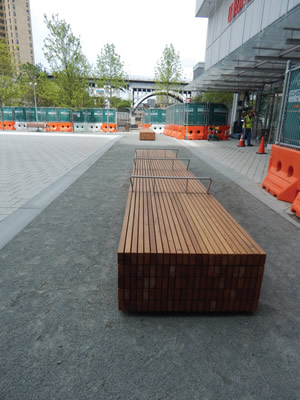

Amenities are attractive and contextual: large, regionally quarried rocks along the pathways serve as benches; there are various native species of trees; and large rectangular blocks provide seating on the perimeter plaza. The blocks are constructed of wood salvaged from demolished light industrial buildings previously on the site.

It is a spot that, along with various other outdoor places on this emerging campus, achieves at least two things. First, the campus in part through its outdoor space reorients the immediate area, establishing a general notion of domain, as Cooper puts it, similar to areas surrounding, but not necessarily a part of, other campuses — for example, New York University in Manhattan. And second, Manhattanville’s inviting outdoor network offers “an opportunity for exchange in a casual, but also programmed way,” between disciplines, among students and between the university and the community, Cooper adds.

Heading West

Rapid City, SD, is a dramatically different setting. Yet Black Hills State likewise, and adroitly, went with contextual outdoor elements for its one-building campus. Chris Wehrle, landscape architect with Wyss Associates, explains that the environmentally friendly design uses drip irrigation to nurture vegetation that includes Buffalo grass and other plants native to the region. Wehrle says that the needs of the campus and the region’s moderately arid climate, which includes very dry periods of the year, necessitate a careful balance between concrete and paved surfaces and a water-hungry landscape design.

A POP OF COLOR. Attention to detail in planning and maintaining the campus landscape is vital. Colorful plantings of flowers and native vegetation add polish to the grounds of Black Hills State University.

Mixed-use development has sprouted up around the university in recent years, but when the site was developed in 2010-2011 its surrounding area was, Wehrle says, “rather barren,” presenting a blank canvas for the landscape. The designer painted that proverbial canvas with understated, yet appealing, brushstrokes. Granted, the campus needed a sizable parking lot, which occupies a significant portion of the property. Still, the rest of the outdoor space is creatively adorned with vivid flowers, which appear in large pots near the main entrance; a variety of well-scaled, lowmaintenance bushes and trees; a short, lighted path with much native vegetation amid river rock; and open space that dovetails with open adjacent parcels.

The City of Brotherly Love

There is not much open space in the street grid occupied by Drexel University and its neighbors in Philadelphia. Yet what open space there is, the university, in a series of modest as well as large projects in recent years, has crafted various solutions, with a number of those projects part of the university’s Public Realm Master Plan.

PHOTO © SCOTT BERMAN

On the smaller scale, adding plantings and furniture to areas such as a campus walkway and near a popular volleyball court for students are simple moves that Drexel’s Niki Gianakaris says “can make spaces much more welcoming.” It works: wooden chairs sit under great shade trees, offering an attractive place to pause just a few feet from bustling city streets; and metal chairs and tables sitting near the volleyball court beside a city sidewalk lend a subtle, cosmopolitan feel to the space.

A bigger move: the $5 million Raymond G. Perelman Plaza at the center of campus. The plaza, which occupies the former site of a city street turned over to the university years ago, provides what the university has called its “town square.” The plaza’s large scale, its furniture and pavers combine with abutting landscaping to make a new, distinctive place.

Meeting a Variety of Needs

PHOTO © UNILOCK

PAVING THE WAY. Hardscape need not be flat and monochromatic. Paving stones and paint are just two of a number of options that can be used to add visual appeal – and even wayfinding – to surfaces that otherwise would appear solely utilitarian. The smallest details can contribute to a dynamic first impression for your campus.

Elsewhere, a number of campuses have also embraced projects that remake plazas while meeting a number of needs. In various instances, institutions have used Unilock paving stones; including projects at Amherst College, the University of Massachusetts Amherst (UMass) and Loyola University in Chicago, according to Unilock’s Elaine Willis.

At Loyola, seen on page 20, a multi-pronged expansion project turned a city street, bought by the institution, into pedestrian paths and a plaza consisting of permeable pavers and native plantings, which help manage stormwater. UMass likewise went with a permeable system that helps manage stormwater while presenting a surface in bands of varying tones. The functional pavers, which vary intricately in color and pattern, also provide visual interest, as is also found in hexagon pavers in three tones on the Amherst College campus. There, the pavers create flowing pathways between buildings and planted areas.

As these examples around the U.S. show, there are many divergent ways to design, construct and equip meritorious outdoor spaces on campuses. One point is shared and evident, however: achievement can start from the outside in.

This article originally appeared in the issue of .