Sustainable Interior Design

CHPS Offers Guidelines to Design and Build Better Schools

Winston Churchill famously said, “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.”

Perhaps nowhere is this sentiment more important than in our school facilities. While we often hear arguments supporting changes in curriculum, technology, and teaching methods to improve our education system, it’s time to really look at school facility design as one of the most important components to effective learning and improving education as a whole.

In recent years, more research has come to light in support of the impact that facility design has on student performance. These studies reveal clear evidence that the physical characteristics of a classroom impact learning, and furthermore, that a link exists between well-designed school facilities and increased academic achievement.

Research Unveils Goals for Design and Function of Learning Spaces

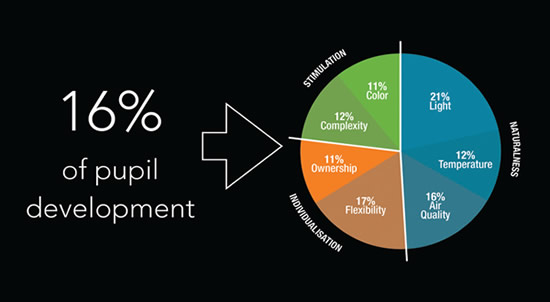

One particularly comprehensive study was conducted by a team from the University of Salford, Manchester, UK. Published in Building and Environment in 2012, the HEAD Project (Holistic Evidence and Design) evaluated 3,766 students across 153 classrooms in 27 schools, incorporating a variety of school, community and building types. Through this evaluation the researchers further identified seven key physical classroom characteristics that contributed to academic achievement and categorized each characteristic into the broader areas of Naturalness, Individualization and Stimulation. Astoundingly, the results concluded that “Differences in the physical characteristics of classrooms explain 16 percent of the variation in learning progress over a year…” To ensure accuracy, the researchers went to great lengths to statistically isolate the effects of classroom design from the influences of other factors. The illuminating summary report, Clever Classrooms, details the research methodology and provides key findings for each of the seven characteristics, offering recommendations for obtaining optimum academic performance.

GRAPHICS © QKA

Clever Classrooms Metric

More recently, a team from Harvard University, SUNY-Upstate Medical School and Syracuse University studied the connection between indoor air quality and cognitive function. The staggering results, published in Environmental Health Perspectives in 2016, found that occupants of enhanced green buildings with superior indoor air quality (low VOCs and CO2 with enhanced ventilation) had a 101-percent increase of cognitive performance when compared to occupants of standard office environments. While this study focused on office buildings, we can deduce that these results have an even greater significance to school facilities, as children are even more susceptible to negative air quality effects than adults.

These examples are only two studies among many that demonstrate the significant impact well designed school facilities can have on student learning. While it’s clear that facility design impacts academic achievement, the challenge can be translating this knowledge into action to create optimized learning spaces for students.

Meet CHPS, the Organization Dedicated to Optimal School Facility Design

The Collaborative for High Performance Schools (CHPS) exists based on research like the two studies presented above to give school districts and architect, engineering, and construction teams the guidance and tools to implement these well-researched strategies for creating optimal learning spaces.

Founded 20 years ago, CHPS has a mission to improve student health and achievement, conserve resources, and protect the environment through better school buildings. It has created a set of research-based standards and guidelines called The CHPS Criteria, which is also the basis for its certification program. Similar to the studies referenced previously, The CHPS Criteria breaks down these guidelines into seven important categories. Within each category there are individual credits and prerequisites, such as daylighting, low volatile organic compounds, or increased ventilation. Each one includes specific metrics for guiding and evaluating school designs to determine whether they can achieve the performance that research has shown to benefit students and teachers.

The 101 prerequisites and credits work together to ensure that every CHPS project meets minimum standards for sustainability and performance in key areas such as acoustics and water use reduction while also allowing the flexibility to accommodate each project’s constraints. CHPS also has state and regional adaptations that embrace regional differences and priorities to make the criteria even more relevant. This balance creates a rigorous and usable tool to guide and evaluate the design of high-performance schools.

Improving Your Physical Environment through CHPS Guidelines and Credentialing

As referenced in the two aforementioned studies and reinforced by CHPS, well-designed learning environments improve learning. School buildings can also be designed to promote sustainability and reduce energy and resource use. The following are examples of areas where CHPS criteria provides guidelines and accountability for school designs:

PHOTO COURTESY OF TECHNICAL IMAGERY STUDIOS

• Light: Adequate and appropriate light was the single largest factor in the HEAD study, and CHPS has four credits to address lighting, both natural and artificial. There have been many studies demonstrating that daylight is best for learning. CHPS prerequisite, IEQ 11.0 Daylighting: Glare Protection, and credit, IEQ 11.1 Daylight Availability, address this issue. Together they provide research-based, qualitative standards for how classrooms and other spaces should be daylit and protected from glare. They also include multiple documentation options for design teams to prove that their buildings meet the requirements of the credit. Credits EQ 13.1 and 13.2 address artificial lighting in areas such as controls, color balance and functionality.

• Air: Another critically important aspect of schools is indoor air quality. CHPS has 10 credits related to improving indoor air quality using a number of design approaches. One of the most important is prerequisite EQ 1.0 which requires that facilities be designed to ASHRAE (American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers) standard 62.1 which details minimum amounts of fresh air and other requirements for indoor air quality. Other important credits are EQ 7.0 and 7.1 Low Emitting Materials. These credits provide a prescriptive approach for specifying materials that emit low or no amounts of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOC), which have negative health impacts on adults and especially children.

PHOTO COURTESY OF TECHNICAL IMAGERY STUDIOS

• Energy: One of the biggest environmental impacts of school buildings is through the energy used to create electricity for the buildings. All of the credits in the Energy category seek to incentivize schools to use less energy and reduce the negative environmental affects that come with that energy use. Prerequisite EE 1.0 requires every school to perform better than state and national benchmarks for energy use. Credit and EE 2.0 provides significant additional points for exceeding those standards further. There are also additional points for being solar-ready and for Commissioning and Energy Management Systems, all of which can help to reduce energy use and environmental impacts.

• Water: Another way in which school facilities impact the environment is through water use. The credits in the CHPS Water category are all focused on helping schools use less water indoors and out. Prerequisite WE 1.0 and credits WE 1.1 and WE 2.1 work together to help schools build well designed water systems that reduce the amount of potable water used in schools. WE 4.1 and 5.1 provide guidelines and incentives for reducing water use for both recreational and non-recreational landscaping. Additional credits are offered for demonstration rainwater catchment and irrigation systems conditioning.

Utilizing The CHPS Criteria, school districts are able to set clear, research-based standards for the design of their facilities and establish requirements for their architects to ensure their school buildings meet these standards. As an option, school districts may choose to have their facilities certified as either CHPS-Designed or CHPSVerified—which includes third-party verification that all criteria are met. This focus on promoting high-performance learning environments, coupled with a flexible approach to documentation and certification, sets CHPS apart as a successful tool for both administrators and designers to create school facilities that positively impact learning for all students.

As the research tells us, the school design and construction community play a significant role in improving our schools. Together with CHPS, we can make a difference in our communities by advocating for better schools for all students.

Cupertino High School New Classroom and Science Lab Buildings

In Cupertino, Calif., three new buildings recently finished construction on Cupertino High School’s campus and they were designed using the CHPS criteria and is on path to receive CHPS Designed Certification. The project provides a total of 22 classrooms, six science labs, and a Career Technical Education classroom to accommodate growing enrollment on this existing campus. High-performance design features, such as daylighting, views, sustainable materials, and high-performance lighting and mechanical systems are important parts of the design. The buildings also have roof-mounted solar panels which provide more than 30 percent of the building’s electricity. Daylighting was a particular focus of the design with large areas of curtainwall glazing in each classroom with exterior sunshades and clerestory windows in the second floor classrooms providing balanced daylighting in many spaces. Pursuing CHPS Designed certification for the project has allowed the district to finance the project with green bonds and meet the community’s expectations for a sustainable facility.

This article originally appeared in the School Planning & Management May 2018 issue of Spaces4Learning.