Energy Management

PHOTOS BY SCOTT BERMAN

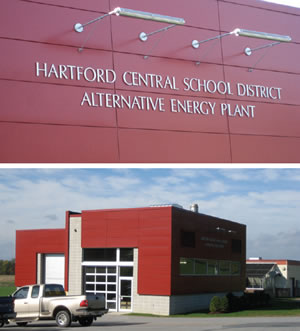

The Hartford Central School District in upstate New York is a small district faced with a big task: what to do about fuel oil bills that reached $123,000 in 2008.

Two years later, the answer stood beside the 479-student, K-12 district’s sole school building in rural upstate New York: a woodchip gasification plant, the first of its kind for a public school in the state.

Hartford’s district treasurer, Joann Searles, and Head Custodian Gary Jones recently guided School Planning & Management on a tour of the plant, our voices echoing as we peered into a great chip storage bunker, which can hold 36 tons — that’s a full tractor trailer load, enough chips “to last approximately six days during coldest weather,” according to the district.

Among the system’s many features, Jones explains: a so-called walking floor that, with a screw-type auger, moves wood chips to a 6.6 MBTU gasifier that reaches 2,200 degrees; a hot water boiler fueled by gas generated by the burning process; and two redundant, oil-fired boilers, one new, as required by the state. Making it all happen took some doing.

In her office, Searles recounts contacts and visits with environmental and energy officials, meetings with local residents and working with the plant’s architect, CSArch, based in Albany, contractor Bast Hatfield, the plant gasifier designer and manufacturer Chiptec, and mechanical engineer JV Warren.

Aside from efficient heating, what have been the results of all that technology three years later? Well, for starters, the district has used between 900 and 1,000 tons of wood chips each year so far, at an average cost of about $38 a ton. That means that the savings in fuel costs have been $70,000 to $80,000 a year over the average price of heating oil in recent years, Searles says. She emphasizes, however, that since prices of both oil and wood chips fluctuate, the better measure is the consumption of oil itself, and in that there’s been a significant difference for Hartford Central schools: Whereas before, the district consumed as much as 38,000 gallons annually, now, one 6,000-gallon oil tank lasts an entire year — and that oil is used only when outdoor temperatures are 40 degrees or above, she explains.

Multiple Savings. The Hartford Central School District, in upstate New York, decided to try the biomass energy alternative in order to save money and use fewer natural resources. They burn wood chips in their alternative energy plant. The savings have amounted to between $70,000 and $80,000 per year, and have gone from burning as much as 38,000 gallons of fuel oil per year to around 6,000 gallons.

Hartford is not alone in the region, according to the Biomass Energy Resource Center (BERC) at the Vermont Energy Investment Corporation, a Burlington, Vt.-based technical assistance nonprofit that works with schools and others “to make the most of their local biomass energy resources.” The roster of other educational institutions that have went to biomass energy plants includes Hotchkiss Academy in Lakeville, Ct.; Burlington High School and Milton elementary and middle schools in Burlington, Vt.; Brattleboro High School, Whitingham Elementary and Westminster Central schools in Brattleboro, Vt.; and Ponaganset middle and high schools in North Scituate, R.I. There are reportedly 47 schools in Vermont alone that use biomass, in fact.

In another alternative energy tack, Camels Hump Middle School in Vermont, armed with federal, state and utility company funds, reportedly installed 507 solar panels in 2011 to provide 25 percent of its energy consumption — the system complements a wood chip heater installed at the school in 1994.

Thus, motivations, opportunities and funding take various forms. Take another example, the design and construction of the Ponaganset schools’ biomass systems — the schools are in the Foster/Gloucester Regional School District, were part of a diverse alternative energy package, including educational programs, which received $984,000 in federal funds in 2008.

BERC reports that schools looking at their options should keep some things in mind: “Certainly, one major rule of thumb for those considering alternatives is to start with facilities that currently use heating oil or propane – those are the most expensive heating fuels and tend to have the best financial rate of return. Another rule of thumb is target facilities with annual heating bills over $20K. Generally, these will have the best rate of return. Lastly, regions like the Pacific Northwest, Rockies, Lake States, and Northeast where there is the combination of local wood resources and cold winters should be targeted for biomass heating.”

In Hartford, N.Y.’s case, it took green to go green. The plant itself — $1-million for the plant and $450,000 for its equipment — was part of a multi-faceted, $15.75-million infrastructure project by the district, with the New York State Education Department funding almost 90 percent overall. A referendum for the rest, $1.3 million, was required.

Some members of the community were concerned about the proposed new plant’s emissions — those emissions would be scant — and that a high, unsightly smokestack would be required — it wasn’t — explains Searles. So district officials reached out to, and met in several public meetings with, local residents who, by a sizable margin, passed the referendum. The project started in April 2009.

Jones admits that he was initially skeptical about the new system. “I wasn’t really optimistic to start with, but after seeing it work…” he gives the new plant a thumb’s up. “It’s saved the school a lot of money,” he says, adding that although “there’s a little more maintenance” required than he had anticipated, “you figure those things out as you go.”

The going got relatively tough here and there. The economic downturn slowed the process and complicated the situation generally. And going to an alternative energy plant, just like constructing and converting to a new energy system whatever form it takes, is not an easy undertaking — “it’s a learning experience,” Searles says.

Sure, there have been challenges to accomplishing such a big task, but things are working out. As Searles adds, “I think it’s fabulous.

Tips for Exploring Alternative Energy Options

Each district exploring alternative energy options has its own needs, opportunities and challenges. No one size fits all. Yet, some tips about the process and results at the Hartford school district may be helpful:

- Do site visits. When considering alternative systems, see firsthand what a range of other institutions are doing, and ask plenty of questions, about technologies, funding opportunities and more.

- Check out all specifications of your and your suppliers’ equipment, to be sure that everything is compatible. Stipulate your related needs in RFPs and contracts.

- Think through scenarios and contingencies. What do the costs look like in the short and long terms, do you have backup suppliers, what’s the plan for maintenance or any emergencies?

- Reach out to others to gain a range of insights early in the process and to help solve problems during it.

- Be responsive. For example, when community members have concerns and questions, get back to them quickly —“don’t leave them hanging,” Searles says.

- Be patient. “Stuff happens,” Searles adds. Those things could include changes in the economy, funding mechanisms, suppliers and other things out of your control. Two expressions that apply: Roll with the punches, and keep your eyes on the prize.

For more information about the kind of approach that Hartford, N.Y. took, see: www.biomasscenter.org.

This article originally appeared in the School Planning & Management December 2013 issue of Spaces4Learning.