The For-Profit Conundrum

PHOTO COURTESY OF GADGETDUDE

There’s been a wash of bad news for for-profit schools over the last few years. Increased competition, government scrutiny and declines in enrollment have hurt the entire sector. Yet, the University of Phoenix — the largest college in the United States — continues to succeed. In fact, its parent company, Apollo Group, recently presented Wall Street with a pleasant surprise. “Apollo managed to turn a profit of 55 cents a share, more than doubling forecasts for a 25-cent profit,” writes Ben Levisohn in Barron’s “Stocks to Watch” column on October 23. Why does everyone remain bullish about Phoenix, and what can other for-profit schools learn from them?

The University of Phoenix was founded in the mid-1970s to address the needs of nontraditional students. Today the school boasts nearly 350,000 enrolled students, 700,000 alumni and 30,000-plus faculty instructors. Eighteen percent of the school’s students are African-American, compared to a national average of 12 percent. Additionally, female students make up two-thirds of the total enrollment at the University of Phoenix, compared to just over half of the overall enrollment in colleges and universities nationwide. The University of Phoenix currently offers associate’s, bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degree programs from campuses and learning centers across the U.S.

But what about the “for profit” stigma?

IT SHOULDN’T MATTER

“The tax status of a school is irrelevant,” explains Mark Brenner, chief of staff, Apollo Group Inc. “University of Phoenix provides an affordable, quality education to nontraditional learners, who today make up 75 percent of the overall college population.”

Brenner also talks about the “learning continuum,” or the training and education workers need to further careers or change professions mid-stream. That’s exactly what David Finnie, Ph.D., did over a decade ago. A doctor of Chemistry, Finnie was working at Xerox, making good money and coming to the realization that he wanted to be more than a scientist.

PHOTO COURTESY OF JAGZ MARIO

PHOTO COURTESY OF JOSE KEVO

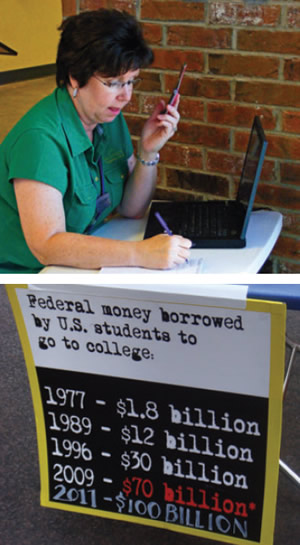

AT WHAT COST? The annual Project on Student Debt at The Institute for College Access & Success (http://projectonstudentdebt. org) tracks yearly figures for graduates of not-for-profit public and private schools. Excluding for-profit schools, 68 percent of the class of 2012 graduated with student loans averaging $27,850. However, of those students who graduated with a bachelor’s degree in 2012, 71 percent took out loans, and that group left school with a record average of $29,400 student debt. The report notes that higher number includes a small number of graduates of for-profit four-year colleges, and they tend to have considerably more debt than students at not-for-profit institutions.

“I recognized I wanted my career to go a different way,” he remembers. “I was in Philadelphia at the time and started classes at Temple University. Then I moved to Oregon and, of course, had to switch schools.” Finnie researched his options extensively. “People advised me that there were two options: attend a top-notch, ivy-league university full time or anything else. If I didn’t go to an ivy league it really didn’t matter if I went to a for-profit school or a more traditional one.”

Since dropping everything and attending Princeton wasn’t a realistic option, Finney decided on University of Phoenix. Although the course work was, in his words, “intense and consuming,” the MBA and is now director of Finance at Radisys Corporation in Hillsboro, OR.

“I would probably attend Phoenix again,” Finnie says. “I got a good education and I’m on track to be a chief financial officer, which is what I wanted. Although there is still a stigma about an online business degree, I’m always careful to let people know I did all of my schoolwork in the classroom.”

EXAMINING THE OUTCOMES

Finnie graduated in 2001. While the attitude about online learning may have changed since then, there is still a cloud that hangs over for-profit institutions. Statistics from the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research bears it out. According to an issue brief published in April: For profits suffer from poor graduation rates, with only 22 percent of students completing college in six years as compared with 65 percent of students at nonprofit private schools and 55 percent at nonprofit public schools. They also suffer from higher loan default rates, with 25 percent of students defaulting as compared to 7.6 percent from nonprofit private and 10.8 for nonprofit public schools. There is also a higher likelihood of unemployment for for-profit alumni.

Yet the problems of dropout, loan default and unemployment persist throughout the entire education system. On top of this, the job market in our informationbased economy has shifted greatly. Today, more than 60 percent of jobs require advanced skills training or education. Further, it’s expected that the fastest-growing jobs in the coming decade will require a college-level degree or higher.

Despite this news, currently only 35 percent of American workers over the age of 25 have achieved a four-year degree. There are approximately 132 million Americans in the U.S. labor force over the age of 25, of whom over 80 million do not have a bachelor’s degree — 50 million of those have never started college and more than 30 million never completed their degree. Brenner stated these statistics in a letter to Senator Tom Harkin (D-Iowa), who has taken for-profit colleges to task.

Not everyone in today’s government comes down as hard as Sen. Harkin on for-profit schools. United States Secretary of Education Arne Duncan recently said: “Let me be crystal clear: for-profit institutions play a vital role in training young people and adults for jobs. They are critical to helping America meet the president’s 2020 goal. They are helping us meet the explosive demand for skills that public institutions cannot always meet.”

The University of Phoenix has taken steps to ensure the success of their students. They require a mandatory University Orientation program. This serves as an introduction to the higher-learning atmosphere for less-experienced students while providing prospective students with understanding of the time and commitment required in order to be successful in their degree programs before they enroll and before they take on debt.

They have also “moved the career discussion from late in the conversation to before students even start,” says Brenner. “Career guidance is available to prospective students online via assessments.” Of the 800,000 University of Phoenix alumni, over 500,000 remain in regular contact with the school. “They come back to check out our career portal job search.”

A CALL FOR OVERSIGHT

Other for-profit schools are feeling the same pressures that University of Phoenix face. There has been some talk of developing a voluntary code of conduct, but that hasn’t materialized as of yet.

It may not be a bad idea. In October, the State of California went so far as to sue Corinthian Colleges, Inc., claiming that they lied to students and investors about job placement prospects, as well as used false advertising and other deceptive practices — such as the misuse of military seals — in their ads. The lawsuit against Corinthian Colleges, Inc., was part of a larger investigation of the entire for-profit college industry, state Attorney General Kamala Harris said in San Francisco in October. Santa Ana, CA-based Corinthian operates Everest, Heald and WyoTech colleges, which have a combined 81,000 students nationwide and 27,000 students in California.

But like any for-profit endeavor, it’s up to the buyer to do due diligence. Often it leads to success.

“I was jumping from job to job,” says Ralyn Miller of Portland, OR. “I barely graduated high school and had some community college, but I was afraid to go back.” At 36, she signed up for the medical assistant program at Concorde Career College and graduated in nine months with straight As. Two weeks later she found a full-time job at a hospital.

“By week two I knew this was the right fit for me. The classes were very hands-on and practical,” she says. “After graduation my self-esteem skyrocketed and I feel like a valuable asset to the community.”

This article originally appeared in the College Planning & Management December 2013 issue of Spaces4Learning.