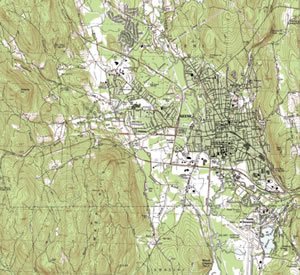

Mapping Safety

PHOTO COURTESY OF DANIEL NISBET

For higher-ed professionals, the first thought prompted by a reference to GIS (geographical information system) might relate to academic offerings, since such programs have been the focus of increasing interest in recent years. But campus leaders are also finding that GIS can serve as a complete information system for analyzing, modeling and displaying campus vulnerability.

“GIS has become an integral part of emergency management in general as well as higher-education emergency management,” says Kenneth Allen, emergency manager at the University of Florida. “Being able to spatially represent data is often key in both planning and response activities.”

Talbot Brooks, director of the Center for Interdisciplinary Geospatial Information Technologies at Delta State University in Cleveland, MS, says that the use of geospatial information technologies (GIT) can be invaluable in supporting all four phases of the emergency/disaster management lifecycle: planning, mitigation or risk reduction, response and recovery. During the planning phase, typical uses include creating evacuation plans, identifying safe havens or shelters, mapping potential flood inundation depths and similar activities related to preparedness.

“Spatial technologies are becoming an indispensible tool for hazard risk-reduction activities because they may be used to model disaster scenarios by bringing together multiple layers of information to assess risks to various hazards, identify vulnerabilities, and estimate potential losses,” he says. This facilitates data-driven decision-making, Brooks notes, by allowing disaster managers to identify potential risk-reduction projects and determine their potential impact in terms of investment costs versus potential losses. Data collected during the planning and risk-reduction phases may often be used to establish the common operational pictures used during the response phase. These map products may be paper-based or integrated with intricate disaster management software solutions. These same systems are often used during the recovery phase to provide map-based progress reports.

“While of tremendous benefit during all four phases, the greatest return on investment occurs in association with the planning and risk-reduction phases as it is far more cost-efficient to prevent a loss than respond or recover from it,” Brooks says.

Advanced Prep

While it has not yet been deployed, the University of Florida has used this approach in developing an online damage-assessment system. In the event of a large-scale incident such as adverse tropical weather, the system allows building emergency coordinators or other staff to input damage information regarding their buildings. The assessment system compiles information for the appropriate facilities area and also displays the damage reports on a campus map, providing university officials with enhanced situational awareness.

“We are working to improve weather preparedness through GIS,” Allen says. “On a basic level this includes overlaying current weather data with university facilities.” Such capabilities are important for Florida, he points out, given that the institution operates facilities across a large state. When forecasts are issued by the National Hurricane Center, for example, it can be determined if any of the institution’s facilities are inside the five-day forecast error cone or under any watches or warnings.

Allen adds that the beta version of the National Weather Service’s Enhanced Data Display (EDD) provides users with the ability to load custom layers into the system, which can be helpful when preparing briefing materials for campus officials. It can be accessed at http://preview.weather.gov/edd.

At Delta State, the technology has been used to develop a detailed campus map, which has served as the basis for the university’s campus hazard mitigation plan. It is also regularly used for event planning as well as developing traffic management plans and evacuation routes, and determining where to place emergency responders.

The University of Utah also uses GIS for planning purposes, according to Marty Shaub, managing director, EHS/EM. One current application is predicting life-safety and economic losses for earthquake hazards using FEMA-approved GIS applications. Another is analyzing the best locations for outdoor Emergency Assembly Points in the case of complete building evacuations. The technology also supports the institution’s emergency operations center in achieving situational awareness.

“The value of GIS in the context of emergency preparedness is knowing the locations and attributes of people, infrastructure and potential risk,” she says. “In terms of disaster recovery, if buildings have been compromised because of an incident, relocation of people, resources and things can be accomplished through GIS analysis.”

Disaster Recovery

“GIS analysts have the knowledge and expertise to apply GIS tools and techniques to aid in natural disaster response and recovery efforts,” says Dr. Stephen McElroy, GIS program chair for Colorado’s American Sentinel University. “GIS provides GIS analysts with the capability of evaluating the extent of the damage and identifying where people may require immediate medical attention or rescue.”

After a natural disaster, such as a tornado, there are several issues that must be addressed quickly, including shelter locations, overall damage assessment, current physical asset inventories and service outages.

Dr. McElroy says that location is the key factor in the recovery process; so determining the number of people affected and coordinating the resources to assist victims can be made a lot easier through the use of GIS. “In times of tremendous need, GIS analysts can play a critical role in matching relief supplies and donations to the precise areas that are most affected,” he adds.

A robust system built in advance could show locations of houses, public buildings, businesses, utility poles, buried cables, storm drains and other features that could be of importance to rescue workers and crews.

GIS can aid with recovery efforts by providing detailed aerial and satellite imagery to assess before and after disaster conditions so that targeted recovery efforts can be planned and coordinated based on the imagery.

GIS also provides the ability to overlay the digital images using GIS software on laptops or creating web applications for mobile device consumption that puts information directly in the hands of first responders and recovery teams. Local government agencies can print hardcopy maps with ancillary GIS data to support to field crews dealing with public utility issues.

Dr. McElroy says that such integration of information can be invaluable, particularly when used with satellite imagery showing before and after views, helping officials know where to concentrate their efforts.

Data Challenges

As use of GIS grows, so will the challenge of handling an increasing volume of information.

“Rapid collection, interpretation and display of data already has become an issue to overcome for emergency response,” Allen says. “The issue now is the large amount of geo-located data produced following emergencies and disasters. This is a good thing, but the value is going to be employing it to create a useful situational awareness.”

He notes that 15 years ago, specialized technology was needed to produce the kind of map everyone now casually consults on his or her smartphone. Today, with geo-location and the burgeoning “Internet of Things,” an overwhelming amount of data is available.

For any institution, GIS is most useful in emergency management when leveraged from its integrated use within the institution, Allen believes. Florida’s robust GIS system is housed with the planning, design and construction department. Since campus emergency management departments don’t typically have the dedicated staff or expertise to maintain standalone GIS operations, similar arrangements might be advisable at other institutions.

THREE GIS TIPS

Delta State University’s Talbot Brooks offers these tips for taking advantage of GIS technology in emergency preparedness efforts:

1. Seek out and read hazard mitigation plans that use this technology. The state hazard mitigation plan for Mississippi is a good starting place and is available online at www.msema.org.

2. Integrate geospatial technologies into everyday use for facilities management, classroom use planning, inventory management and similar activities. Such use significantly increases return on investment while familiarizing the broad audience who are potential users of spatial technologies during a crisis with the systems.

3. Understand that the data and plans developed should extend into the greater community, since disasters don’t respect campus boundaries.

Brooks may be contacted at [email protected] for advice on the use of spatial technologies for emergency preparedness and other purposes.

This article originally appeared in the issue of .