Restrooms for All

PHOTO COURTESY OF ASI GROUP

On February 22, 2017, President Trump revoked federal guidelines specifying that transgender students have the right to use the public-school restroom that matches their gender identity. While this Dear Colleague letter addressed the K–12 world specifically, the implication for colleges and universities was clear: this administration is opposed to expanding LGBTQ rights, starting with the restroom.

While certainly a setback, transgender inclusivity continues to grow on campuses. Today approximately 150 college and universities offer some sort of gender-neutral bathroom and over 200 provide some type of gender-neutral housing, according to Campus Answers. “Students are demanding these spaces as well as faculty and staff,” says Anita Picozzi Moran, FAIA, TreanorHL Architects. “The movement to provide all-gender spaces is well underway.”

Kurt Haapala, partner, Mahlum Architects, also reports momentum. “Four years

ago, I had clients that felt their clientele wasn’t ready,” he says. “But last year they called and said they’re ready to be more gender-inclusive.”

The toilet has long been a battleground for equity. Restrooms were first sex segregated in the late 1800s, as more women began entering the workforce. In 1990, the Americans with Disabilities Act demanded stalls and sinks that accommodate people with physical limitations, like wheelchair users. “Public restrooms are not just toilets,” writes Harvard Law School Professor Jeannie Suk Gersen, in newyorker.com. “For more than a hundred years, they have implicated questions of who really belongs in public, civic and professional life.”

So, do transgender and non-binary people feel like they belong? Results from the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey suggest not: 59 percent say they avoid using the bathroom altogether, 31 percent avoid eating or drinking and 8 percent report having had a kidney or urinary tract infection from avoiding restrooms.

PHOTO © CIUD

Those results, however, target the general population. The story changes a bit on higher education campuses. Bound by the protections granted in Title IX and mission statements that call for inclusivity, colleges and universities have been tackling equity and diversity issues for years. Some of the solutions, while well intentioned, turned out to be tone deaf. Haapala recalls a story about a transgender student who was quarantined to a special bathroom. “They felt the university outed them to the whole community,” he says. “It was heartbreaking. We can do better.”

Inclusivity, With a Focus on Privacy

Instead of creating special places that single out individuals, architects and schools are moving towards a more equitable solution with benefits for everyone: privacy. This trend has been growing for years; witness the demise of the gang shower. Once ubiquitous, a bare room with rows of shower heads seems unthinkable today. Even curtained-off shower cubicles feel retrograde. “The shower paradigm has completely changed,” says Jason Boyer, architect, Studio Ma.

In answer, schools have embraced privacy by offering shower pods. A more personalized concept, these individual shower rooms allow users to shower and change in complete privacy. Boyer has designed several locker rooms with pods and reports that students now expect them, especially in student-funded spaces. “Old-style locker rooms were not highly used,” he says. “Culturally we’ve moved on.”

Toilet stalls represent the next natural step. The one-inch wide partitions offer limited visual privacy (Is there anything worse than making eye contact with someone through the door gap?) and no acoustic cover. For students demanding more hospitalitydriven spaces the toilet stall feels like an unpleasant and invasive place to take care of necessary functions.

Partition manufacturers are aware of the issue and developing solutions. “We offer nearly floor-to-ceiling partitions that have overlapping doors and no pilasters,” says Cyrus D. Boatwalla, director of marketing, ASI Group. “There are no sightlines in from the side. It really creates the sense of a room.”

Some forward-thinking schools are trying a different approach. They’re replacing the gendered restroom with a unisex space that offers lockable shower/toilet rooms and a common sink/mirror area. “We’ve gotten rid of the urinals and added lounge areas, some with soft seating,” says Haapala. Think oldschool women’s vanity areas, but for everyone. “It’s a place to bond with your classmates while you get ready.”

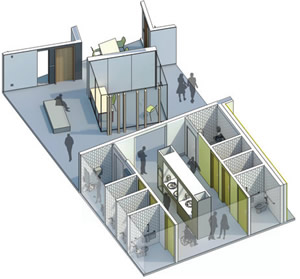

RENDERINGS COURTESY OF MAHLUM ARCHITECTS

ALL ARE WELCOME HERE. An approach to all-inclusive restroom design by Mahlum Architects involves the disappearance of all existing “gang-style” bathrooms — replaced by individual toilet rooms with full doors open to a shared space for wash basins and drinking fountains. Two ways in and out eliminate the feeling of entering into a “dead-end” room, increasing safety and security. Use by staff and students will further enhance safety. Signage with a simple pictorial representation of a toilet, not the ubiquitous “his” (pants), “hers” (skirt) or “theirs” (both), the toilet room is open for use by all.

Haapala has successfully used a variation of this model in a retrofit. A redesign of a dorm building at San Diego State was limited by its concrete construction. Haapala created gender-binary bathrooms and showers but united them with a common sink/vanity area. “There was no soft seating but the students still love it,” he says.

Barriers to Inclusivity

The privacy these spaces offer comes at a cost. Boatwalla reports that European-style, floor-to-ceiling partitions use more material and different hardware than standard partitions, making them more expensive. “They’re newer, so there might also be a learning curve for installers,” he adds.

Individual toilet/shower pods, on the other hand, are actual rooms with studs, drywall and ventilation. Building them “is not cost-neutral but it’s not a budget buster either,” according to Haapala. “You need more real estate.”

“It’s hard to say if these spaces are more expensive,” counters Picozzi Moran. She points to an athletics project for the University of Texas, Austin that called for an all-gender restroom. She designed multiple private cubicles with a common sink area, calling it, “more cost efficient and more space efficient.”

Building codes present yet another barrier. Still mired in the gendered thinking of the late 1800s, plumbing codes demand separate spaces for men and women. In smaller cities, code officials don’t have the latitude to make broad interpretations, according to Haapala. “Lots of education has to happen early in the process to help them find precedence,” he says.

But change is coming. The AIA reports that the 2018 International Building and Plumbing Codes include new code provisions for gender-neutral restrooms that were first proposed by the AIA. States and local jurisdictions can adopt the code now.

This article originally appeared in the issue of .