Net Positive

PHOTOS BY SCOTT BERMAN

“This building is a living, breathing thing of its own.” That’s what Shawn O’Connor, assistant principal of Sandy Grove Middle School in Lumber Bridge, N.C., says about the new building’s real-time energy monitoring and automatic systems. It’s a net-positive facility — Sandy Grove produces more power than it consumes, feeding electricity back into the local grid.

Opened in September 2013, Sandy Grove’s students, faculty and administrators have thus wrapped up their first year in the new building. So how have things gone? School Planning & Management toured the school recently with O’Connor and his colleague Tonja McGill, principal intern — both were upbeat.

As with any new building, or older one for that matter, there are “little kinks here and there,” such as some motion-detector lighting that would turn off during periods of stillness in class lessons, O’Connor says, “but we were in on the first day of school and that’s all that really mattered.”

Sandy Grove Middle is a leased, public school of the Hoke County school district. The building was developed, financed and constructed in a public-private partnership between the county; the district; owner/developer First floor and a sister company, SfL+a Architects; construction manager Metcon; and Lumbee River Electric Membership Corporation, a utility cooperative. The district leases the building from FirstFloor.

PHOTOS BY SCOTT BERMAN

The area is growing quickly: the district created the school from portions of two area middle schools near or at capacity, with a mix of faculty and staff from both schools and elsewhere. The district clearly saw the challenge of establishing a new school as an opportunity for a progressive step forward, and the result: a $15-million building that, instead of generating electric and gas bills, will continue to generate about 33 percent more electricity than it’s consumes, O’Connor says; with another estimate reportedly as high as 42 percent. According to the school, the district “can expect to save $16 million in energy costs over the next 40 years.”

Administrators and faculty, aside from acclimating students to the new facility and its systems, have fielded many inquiries about the building. Educators from other districts in North Carolina and from out of state have visited to examine Sandy Grove’s systems and overall design.

Sandy Grove, a 76,000-square-foot, LEED Platinum standards building, has separate halls for grade levels and other spaces bathed in plenty of natural light. Among many other features, the new school is served by 2,300 solar panels; a custom-controlled generator with 600 khw and demand response; fixtures that slash water consumption by 30 percent; advanced geothermal, LED lighting and air quality systems; Energy Star appliances and equipment; individual room thermostats; open, adaptable spaces; and ergonomic furniture. The impression of a forward, pragmatic design starts before entering the building: a dramatic line of 20-foot-high passive solar panel towers lead toward the main entrance, giving the impression of a parade of functional sculptures. There are also designated parking spaces for electric charging.

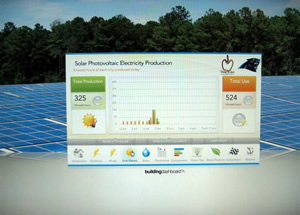

Walking through the halls of this typically bustling middle school, one encounters the building dashboard, which provides a real-time gauge on what’s happening in terms of electrical load, photovoltaic production, water consumption, and geothermal cooling and heating kBtu/energy use. In another dashboard measurement, when School Planning & Management visited the school, it had cost $4.91 to cool the entire building at that point on a warm day — it was a late morning in May, and hours of sunlight lay ahead with the prospect of pushing that modest deficit into the plus column.

And it’s not just about the building’s systems. O’Connor and McGill both talk about the importance of amplifying the green through being proactive in aspects such as training building occupants in how to best use the technological features. Doing so can go a long way toward making procedures easier and smoother from the get go, and over the long term helping those systems perform at or near their peak. A key result: keeping daily routine focused on education.

Proactively pointing out any maintenance or performance issues right away is also important. As McGill points out, “At some schools, if there’s a problem, it’s not brought to the immediate attention” of the administration and, in turn, the contractors.

PHOTOS BY SCOTT BERMAN

Charge It. One of the many unique features at Sandy Grove Middle school are the designated parking spaces where teachers and staff can charge electric vehicles. These features have generated a lot of interest and brought educators from other districts in North Carolina and from out of state to examine Sandy Grove’s systems and overall design.

There are other dynamics at work. As McGill describes while walking through the building, “I see this as one example of how a school building can be used as a learning tool for schools.” The systems dovetail with STEM, she explains, providing real-world applications in those disciplines, as well as a model that young people could use in various ways, whatever form they take, in the future.

And finally, even though Sandy Grove Middle is in North Carolina, not Missouri, there was an understandable “show me” attitude locally as plans for the facility progressed, says O’Connor. The technologies and financing, after all, are novel. Yet word around the district about the new facility is reportedly quite positive.

In an anecdotal but encouraging incident, O’Connor reports that while stopping in at a nearby convenience store for coffee recently, an area resident also in the store learned he was a teacher at Sandy Grove and said, “ ‘Oh, that’s the school that sells back the energy, right?’” Shawn answered in the affirmative, with the resident replying, “ ‘Well, I’ve lived in Hoke County for 30 years and I know a good thing when I see it.’”

Tips about using an advanced green school building:

PHOTOS BY SCOTT BERMAN

Solar Sculptures. Among many other features, the new school is served by 2,300 solar panels. The impression of a forward, pragmatic design starts before entering the building — a dramatic line of 20-foot-high passive solar panel towers lead toward the main entrance, giving the impression of a parade of functional sculptures.

- “Learn as much as you can about building upfront,” says Sandy Grove’s O’Connor — and that goes for “everyone,” including staff, custodians and students.

- Establish training procedures for staff, not only in terms of using advanced building systems, but also in how to communicate about the building and its systems with the surrounding community, with other educators, and with media, which may also be interested.

- Monitor and reinforce best practices and behaviors — energy efficiency and sustainability are not just about automatic systems, but also in being proactive. Remember that it’s an ongoing process.

- Be vigilant. Point out any problems with a building feature or system. Nip such problems in the bud, urges McGill, who adds, “Don’t allow things to build up.”

- Provide transparency: Let the community in — on the facts, the vision, the plan, the features, the construction, and the completed building.

To see Sandy Grove’s real-time building dashboard, visit buildingdashboard.net/hcs/#/hcs/sandygrove.

This article originally appeared in the issue of .