Beyond the Playing Field

IMAGE COURTESY OF HOK AND S/L/A/M COLLABORATIVE

A transformation is underway at Notre Dame Stadium in South Bend, IN. It’s the Campus Crossroads Project, a groundbreaking planning and design initiative that is converting the historic stadium into a year-round hub for academics, athletics and student life.

The project, the largest building endeavor in the university’s history, brings new loge boxes, press facilities and club seats to the 1930s-era stadium that will optimize its flexibility for multipurpose events and academic uses on non-game days. But Campus Crossroads is much more than that. The project adds three massive new buildings to the west, east and south sides of the stadium, bringing more than 800,000 square feet of new classroom, research, student-life, fitness, multimedia, performance, meeting, event and hospitality space to the university. The project has the additional benefit of drawing students to the stadium on more than just autumn Saturdays and strengthening the facility’s connectivity to the surrounding campus.

PHOTO © CHRISTY RADECIC

“The integrated nature of this project will maintain the compact walkability of campus, facilitate deeper connection and collaboration across the various units of the university, and offer an exciting addition to what we believe is the best on-campus student learning experience in the country,” noted Rev. John I. Jenkins, president of University of Notre Dame, when the project was first unveiled.

Campus Crossroads is the largest example of this new type of hybrid facility sprouting up on university campuses that connect academics, athletics and student life. And as the facilities race continues on campuses, administrators can expect to see many more in years to come, says Doug Barraza, a senior project manager with HOK, whose Sports + Recreation + Entertainment practice was the sports and hospitality consultant to architect-of-record S/L/A/M Collaborative on the project.

PHOTOS © CHRISTY RADECIC

The largely untapped synergies existing between separate and diverse programs on college campuses have the potential to change the way university facility projects are managed, financed and programmed, notes Barraza.

“For a long time, athletics and academics have approached facilities projects fairly independently, but over the last several years we’ve seen a fundamental shift in that model,” Barraza says. “Administrators overseeing facility development are challenged to balance the facility needs of the institution’s academic departments with the revenue generated from collegiate athletics and the importance of building a vibrant student life. What seems like a difficult balance can actually be a great source of opportunity for every campus planner, architect and administrator.”

The Evolution of Multipurpose Venues

For decades, the siloed departmental and planning approach within university systems resulted in projects that were single purpose. Academic buildings served only academics. Athletics served only athletics.

Like the University of Notre Dame, a few U.S. colleges recently have begun to shake up this traditional approach to facility planning and design, creating multipurpose buildings inspired by commonalities in the programmatic needs and connections among various departments and programs. Northwestern University’s new Ryan Fieldhouse and Walter Athletics Center, designed by HOK in association with Perkins + Will, is one example. The complex, built in Chicago along the shore of Lake Michigan, relocates and consolidates practice, training and academic services for multiple sports programs, including football, soccer and lacrosse. Additionally, the complex provides recreation and athletic facilities for the entire student body.

IMAGE COURTESY OF HOK

Miami of Ohio’s new Athletic Performance Center (APC) takes a similar approach, consolidating resources to give all student-athletes access to state-of-the-art strength and conditioning, sports medicine and a weight room that serves the football team in addition to women’s field hockey, softball and tennis. Like Notre Dame’s Crossroads Project, Miami University’s APC is incorporated into the school’s football stadium, bringing year-round activity to the Oxford, OH-based facility.

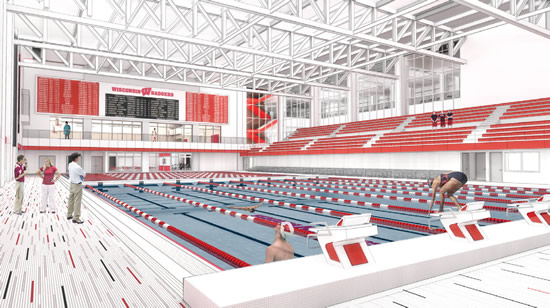

University of Wisconsin-Madison’s (UW) renovation of its Southeast Recreational Facility (SERF) provides an example of a student life and recreation building expanding its usage to also accommodate college athletics and training. When completed in 2020, the SERF is expected to serve as a campus hub, with fitness facilities for all UW students, wellness-focused amenities like a dedicated personal training suite and a new competition Aquatic Center that will become the new home of the Badgers swimming and diving teams.

How to Grow Consensus, Create Synergies

As schools like Notre Dame and Wisconsin have shown, opportunities for collaboration between administrators and athletics can elevate collective campus facility needs to create projects that serve a broader set of students. But how does a school move toward creating one of these hybrid, multipurpose facilities?

IMAGE COURTESY OF HOK

The process can be challenging. A broad set of users must be engaged early to build consensus and better understand synergies and challenges. Campus architects and planners are often best equipped to lead the charge, orchestrating conversations with key decision makers and bridging potential silos well in advance of the project moving forward. Often, too, it takes bringing in early an outside design and consulting team that has experience on these types of projects and can help all stakeholders comprehend and imagine the full scope of the project. Other factors to consider include:

• Funding. Many of the challenges driving this change are related to funding and the historical differences in funding mechanisms for projects — particularly between athletic and academic facilities. Projects that might be easy to fundraise for might not be the projects the campus most needs. The multipurpose facility project provides the greatest opportunity to reconcile this, creating a greater set of resources to draw from.

• Programmatic considerations. There are real programmatic challenges in bringing together diverse groups on campus. Each entity has very separate and specific needs. For example, basketball and football coaches will be concerned with the player path of travel in a training facility and want the adjacencies of the space to support the way they run their teams. An academic administrator will have much different concerns about adjacencies, wanting to minimize distractions and ensure the space is designed to be conducive to learning.

• Security. Security and privacy present another challenge. For example, if a football stadium interfaces with academic and recreation spaces, designers must think strategically about how to create multiple entry points and wayfinding that supports both event- and non-event-day activities. Flexible rings of security should be incorporated to keep professors or students from entering the stadium seating bowl while still allowing for tours or other revenue-generating non-event-day activities beyond academics. In a shared training facility and recreation center, window treatments, operable walls and sophisticated security technologies support flexibility. These options create necessary privacy for teams during meetings or practices while also creating connectivity when team spaces aren’t in use.

What’s Next

“We often talk about the unprecedented value of spontaneous interactions in the research world. Campuses are no different,” says Chris DeVolder, managing principal of HOK’s Kansas City office, who has worked on numerous multipurpose facilities on college campuses, including Notre Dame’s Campus Crossroads. “When we bring professors from different fields together with researchers, administrators and athletes, we begin to uncover what’s best about universities — the diversity of thought processes and experiences.”

Schools can better establish themselves as research institutions, for example, by bringing training, research and healthcare into one single facility that encourages interdisciplinary collaboration. Or, by the same token, a hybrid facility can create an unprecedented hub for student life by bringing together recreation, athletics, a student union and academics.

“At its core, the collaborative approach results in buildings that work harder, do more and better serve the entire student body,” adds HOK’s Barraza.

Forward-thinking universities that have embraced this hybrid approach to facility design recognize the campus master plan as a living document that can evolve with the needs of the university. Yes, it’s true that pooling resources can create new and sometimes surprising neighbors. These partnerships born from facilities projects can also pave the way for future collaborations that ultimately ensure the long-term health and viability of the college campus.

This article originally appeared in the issue of .