Focus on the Silent Middle

Safety and educational appropriateness are the highest priorities for school facilities. Their locations, accessibility, security, sustainability, and quality have a significant impact on a community. That’s why community engagement is an essential part of facility planning.

Anyone involved in facility planning knows it’s extremely rewarding to advance student learning in the modern era, but they also know it’s a process riddled with politics. The political nature of facility planning expresses itself differently in different communities, but it tends to follow similar patterns.

The Making of an Opinion

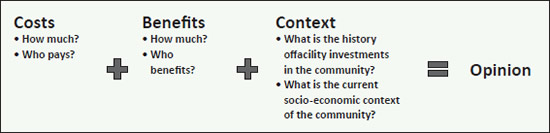

Most political debates stem from the lack of a shared understanding regarding the realities impacting facilities. Differing opinions often originate from the following:

Stakeholders invariably have different concepts about how much facilities cost to build or maintain and where the money comes from. Similarly, the probable benefits of a particular plan and who will benefit (and when) may be unclear. Stakeholders also have very different life experiences that influence their beliefs about “the right thing to do.” Beneath different understandings of costs, benefits, and context lay trust, or the lack thereof.

Limited Resources: The Squeaky Wheel Shouldn’t Get the Grease

A single facility planning cycle cannot lead an entire community to a shared understanding of a facility plan’s costs and benefits, let alone in a way that is mindful of every stakeholder’s context. A single cycle can’t repair trust that may have been broken in the past either. With limited time and resources, districts must understand that some stakeholders will never be completely supportive, and some will be against them.

The key to resolving political opposition is educating the community. Assuming a facility plan is based on solid data, sound investment logic, and responds to the needs of the district and community in a sustainable manner, the best way to counter opposition is to cultivate an understanding of the data and logic used to create the plan.

Some stakeholders believe all capital investments lead to higher taxes, while others don’t recognize there is a limited amount of money to spend. Individuals who embody these extremes tend to be the hardest to educate and the loudest voices in a community.

Many districts allow these “squeaky wheels” to monopolize the conversation in their communities. They spend an extraordinary about of time and money attempting to placate these squeaky wheels, who ironically, are the least likely to change their minds. Instead, districts should focus on the silent middle—stakeholders who are mindful about forming an opinion.

Consider this Approach

Assuming a facility plan is based on sound data and logic, and assuming it supports long-term sustainability by accommodating increases in enrollment and evolving trends in education, technology and community needs, districts should concentrate their efforts on educating the silent middle.

Help them understand how much money is available to spend on facilities district-wide, how much a particular plan costs, and who will benefit. Define specific characteristics of sustainability, so the community understands the lasting value. Perform this outreach with diligence to reach as much of the community as possible, while embracing the fact that 100-percent consensus is impossible and that historical wrongs, when present, cannot be erased overnight. Most of all, understand that if the hardest stakeholders to convince consume most of your time, they have already won.

For more information about the power of community engagement during facility planning, contact David Sturtz at [email protected].

This article originally appeared in the School Planning & Management May 2018 issue of Spaces4Learning.

About the Author

David Sturtz has more than a decade of experience as a teacher, administrator, educational entrepreneur and strategic planner. He has overseen the instruction of thousands of students, and he has hired and managed hundreds of teachers and supplemental instructor. Today, David serves as a project director for DeJONG-RICHTER a leading school facility planning firm. Both David and the firm are members of the Council of Educational Facility Planners International (CEFPI).