Transportation Tales

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

A campus transportation program has many elements, including university fleet management, personal vehicles, shared vehicles, shuttles, university transit, bicycles, pedestrians, parking supply, loading/servicing of buildings, curb areas, transit loading areas, sidewalks and multiuse paths.

Hmm, how to manage all those elements and ensure a strong transportation program? Well, it may begin with a Transportation Demand Management (TDM) master plan, the purpose of which is “to align the longterm goals and adequacy of the mobility plan to the long-term projections and goals of the campus, typically formalized in a campus master plan,” says Jon Efroymson, senior parking consultant with Walker Parking Consultants, and based in Indianapolis. “Those goals may range from reducing the amount of assets devoted to parking to unifying a disconnected campus to promoting various ‘green’ goals. The result typically is a ‘less auto-centric’ campus.”

In addition, Efroymson notes that a TDM master plan seeks to introduce “choice” by revealing and charging an amount closer to the “true cost” of parking in order to rationalize the cost of alternatives. “A TDM plan should consider all available linkages and elements of mobility,” he says. “Linkages include all methods of transportation from points of origination to destinations by roads, rails, bus routes, bikeways and walking paths. Elements include unbundling and charging appropriate permit fees and rates, while providing alternatives and subsidies for those alternatives. Alternatives may include, but aren’t limited to rules (like prohibition of freshman resident vehicles), cafeteria plans and subsidies for transit, shuttles, carpooling, car sharing (Zipcar), van pooling, bicycling and walking. Some of these alternatives must be coupled with a guaranteed or emergency ride home program and occasional-use permits.”

Take Time to Study the Options

In 2012, Indiana University Bloomington (IU) conducted a TDM study, for a number of reasons, including, but not limited to, reducing the number of cars on campus, creating a more sustainable campus and to determine if it was feasible to outsource parking. Kent McDaniel, transportation liaison and demand manager for the university, notes that the study showed it was feasible to outsource parking, but the university’s new CFO did an analysis of the study and determined there was no real advantage, and administrators decided they could raise more revenue themselves, if that was what they chose, without losing the flexibility they had in managing everything themselves.

Otherwise, McDaniel wasn’t too surprised by anything the study showed. “Our biggest fault was that we had many of the elements already. They simply weren’t centralized or organized, and we didn’t promote them, so a lot of people weren’t aware of our services,” he explains. “Now we have a budget to organize, package and promote our services, and we’ve already begun implementing changes.”

Already McDaniel’s transportation team has produced new brochures, improved the website and sent emails. He indicates that they’re planning a promotional blitz this summer to coincide with the new fiscal year, which starts on July 1, and which is when new parking permits are issued.

One new element being introduced is a Commuter Club. Some of the member benefits will include prize drawings, free rides on the Bloomington transit bus and the ability to purchase additional one-day parking permits at $4 as opposed to the current $8 rate. Also, academic units or departments having an outstanding percentage of participants will receive a catered lunch. “Our goal is to start modestly and build up the program,” says McDaniel, who spends 50 percent of his time implementing the TDM, “while becoming more green and efficient.”

PHOTO COURTESY OF INDIANA UNIVERSITY CAMPUS BUS SERVICE

Start Small, Acquire Buy-In

As IU’s program indicates, when it comes to implementing strategies indicated by a TDM, most begin with the low-hanging fruit — that which produces the biggest gain for the least cost. For example, says Efroymson, “Car-sharing is provided by the vendor, making this option relatively inexpensive. Ride boards and signed preferred parking spaces promote carpooling at relatively low cost. Cafeteria plans may incur mid-level costs. High-cost programs include expanded transit options and fare subsidies. However, the construction of parking facilities typically is the highest cost option of all.”

Implementing TDM results alone doesn’t make for a successful transportation program. Susan P. Sloan-Rossiter, LEED-AP, ENV-SP, a principal at Bostonbased Vanasse Hangen Brustlin, Inc., offers three strong contributors. “One key to the success of a campus transportation program,” she says, “is commitment from the highest level of administration. There needs to be a strong statement from the administration toward a more sustainable environment because changes in behavior or philosophy fall from the top down.

“Another key,” Sloan-Rossiter continues, “is that it needs to be comprehensive, with attractive options when compared to driving alone. For instance, if you want to promote bicycling, you must be committed to putting in infrastructure to support safe and convenient cycling.

Third, Sloan-Rossiter offers marketing as a contributor to success. She notes that campuses often have programs in place but they aren’t communicated broadly enough.

Positive Reinforcement

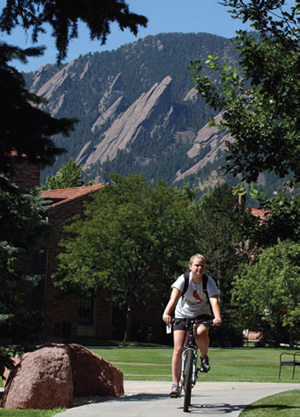

One university that boasts a strong transportation program is University of Colorado Boulder (CU-Boulder). David Lieb, director of Parking and Transportation Services, advises that success comes from having strong incentives, as opposed to disincentives: “You should offer good alternatives.”

PHOTO COURTESY OF UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO BOULDER

One of the alternatives the campus offers is paid transit passes for every faculty and staff member. He notes that not every person uses his/her pass, which the university purchases at a reduced rate, but the cost balances out. “You have to decide if it’s more cost effective to provide an alternative than to provide more and more parking,” Lieb says. “There are higher and better uses for land than parking, but the administration has to make a conscious decision to that end. It costs millions to build a parking structure, to which you are committed for the next 40 years, so it’s not a tough sell, especially in a financially constrained environment, to determine that it’s more cost effective to pay transit fares than build a parking garage.”

Another program CU-Boulder offers includes carpool matching. Here, Lieb indicates the need for security blankets — solutions for employees without a car on campus needing transportation at a moment’s notice for, say, a family emergency at home. To that end, the university offers a guaranteed ride home program. “We have given rides of an hour or more in one direction to get someone where he or she needed to go,” he says. Another program is providing one-day parking permits, which is ideal for an employee who may need to leave work early one day for an appointment and will return to his/her normal sustainable commute the next day.

In the end, a successful campus transportation program is “one that best facilitates access and mobility within the systems that are available or that can be structured,” says Efroymson.

That facilitation begins with convincing senior administration that TDM is a solid investment because avoiding future expense is genuine savings. “It can be tough in a time when campuses are saying, ‘We’re in financial trouble right now,’ to determine that spending a little more now will save you millions and millions later,” Lieb sums. “That sale has to be made internally because, as an institution, you’re going to have to make some kind of an investment.”

A Campus Transportation Program Can Have Community Perks

A strong campus transportation program can have perks for the community in which the campus is located. Community transit is one example, says David Lieb, director of Parking and Transportation Services at University of Colorado Boulder. “Transit is a money-losing operation in any community in that the typical fare box recovery pays for between 15 and 40 percent of the cost of providing public transportation. It varies depending on the agency, but it’s going to be less than 50 percent.”

Therefore, without other funding sources, public transit can’t exist. On top of that, it’s difficult for transit agencies to increase ridership because, to do that, they have to increase routes and make them more convenient. It’s a Catch-22: without service they don’t get demand, without demand they don’t get service. However, when a university purchases transit tickets for its employees, it injects a pool of riders into the transit system, breaking the Catch-22, and changing the face of public transportation.

This article originally appeared in the issue of .